Table of Contents

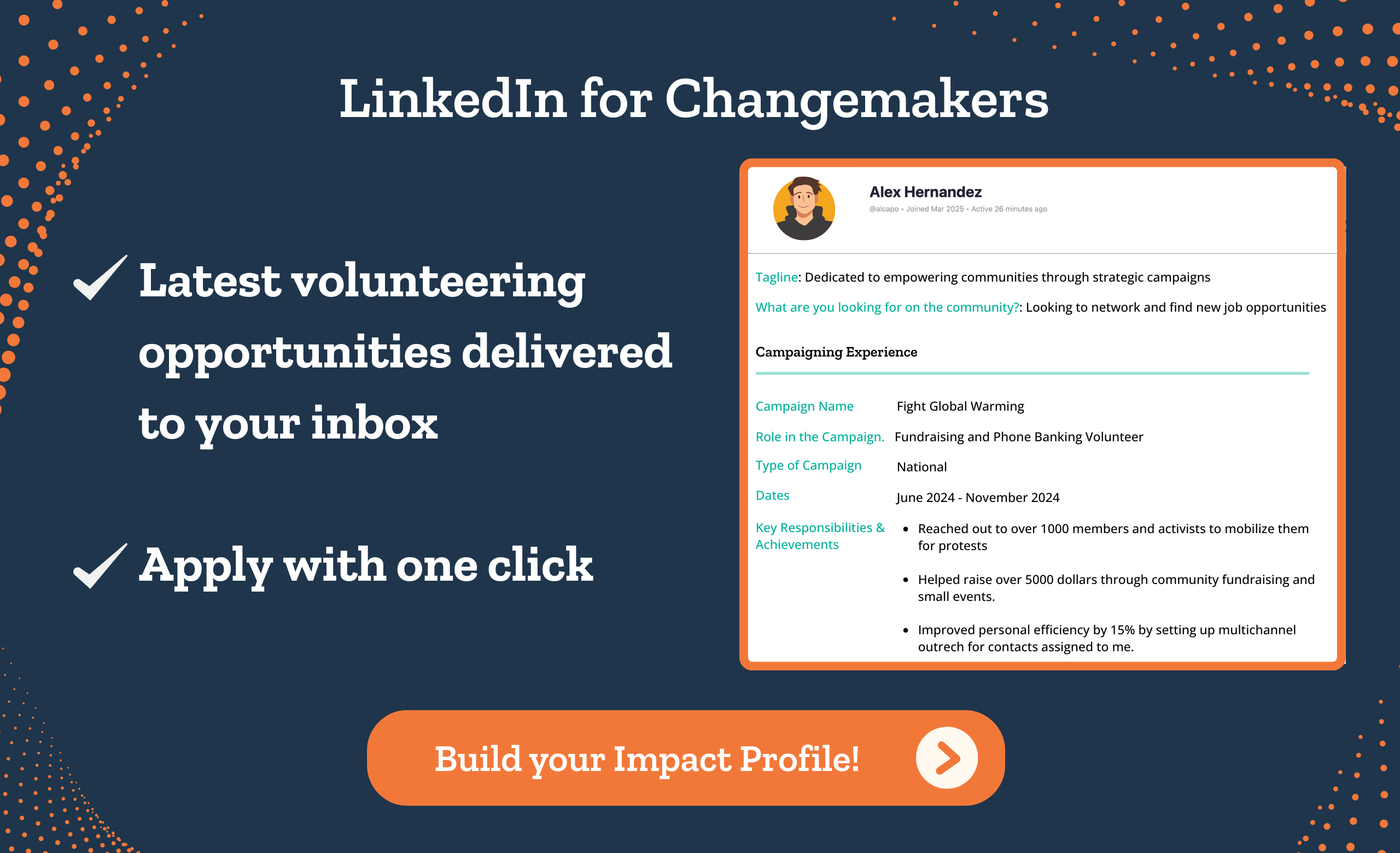

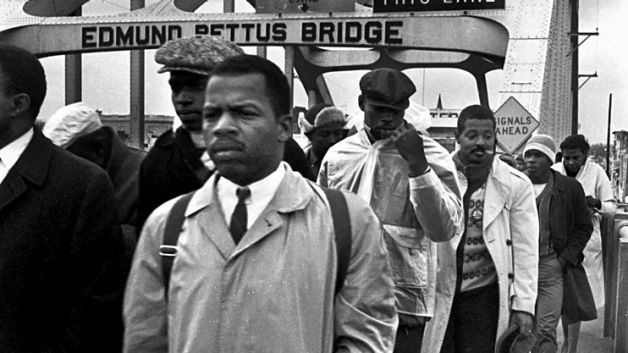

A while ago, I remember watching President Obama’s address at Selma, commemorating the 50th anniversary of the African-American community’s historic march for voting rights.

A President, more than any other, defined by his oratory skills, Obama has given plenty of powerful, era-defining speeches over the years, from the one that propelled him to the public eye in 2004 at the DNC to his final address as president in 2017.

But this speech at Selma was something special. It reflected the complicated history of race in the country and expressed a profound hope for the future. It was one that only the first black president of the United States could have given. And by all accounts, it was the perfect speech by virtue of bearing all the hallmarks: Style; Substance; Impact.

Even years later, watching it through a screen, one can not help but feel the solidarity that those in attendance at that 50th-anniversary event must have felt.

Now, there are a number of reasons you may be in want of a speech. After a resounding election victory. Or after a disastrous defeat. To bring an audience to their feet in celebration. Or calming them in the aftermath of a tragedy. Whatever the cause, here are the aspects you can use to construct one.

Deconstructing a great speech

Let us take a closer look at how to write a political speech through the lens of Obama’s speech at Selma:

Style

When we look at the renowned orators in history, we see masters of both the written and the spoken word. Lincoln’s ten-sentence Gettysburg address holds the same weight today, despite there being no audio recording. As may the speech at Selma in the future, in the way it was masterfully constructed.

Substance

Needless to say, beauty withers under a scrutinizing gaze. The same could be said for a speech. Every great feat of oration has always backed its elegant prose with a sturdy backbone that is its theme. In Selma, the theme set forth was that of racial justice.

Impact

What impetus does your speech provide its listeners? What should the receiver ruminate on as they lay awake in their beds that night? That is how you will measure the impact of your speech. If the audience can take something concrete, something worthy, you will have fulfilled this condition away from the venue.

In Selma, it made the youth in the audience think – What excuse do we have not to vote when our parents and grandparents fought so hard for our right to do so?

Now we take a deeper look at how to bring these three components to the forefront of our speech by examining each individual element. Not all of these elements may be present in all speeches, nor are they necessary, but they are helpful to have at hand.

Elements of Style

The selection of words

Linguistic studies define the concept of “word choice” or “diction” as a critical element in communication theory.

One word can paint an entire picture. The work of word selection is the work of relating to your audience and evoking powerful imagery in their minds.

The solemnity of the occasion necessitated the use of a more formal speech by Obama but did not limit him to it. With phrases like “the fierce urgency of now” and “the roadblocks to opportunity” combined with the occasional informal language, he adeptly managed to weave more abstract concepts with the ground reality.

The tone of delivery

Speakers do not always write their own speeches. If that is the case, a speechwriter should be aware of the speaker’s mannerisms and how they talk and play to their strengths. Look at their past speeches for moments of greatest impact.

Pay attention to their tone, tenor, regional accent, and minor idiosyncrasies as they speak. If the speech is made for a specific audience, it is good to take note of local colloquialisms as well.

The structuring of sentences

The best speeches are texts that are beautiful to both hear and read. A surprisingly effective measure towards this end is to read the speech aloud in the process of writing. If it sounds natural, you are on the right path.

Obama alternates between short and long sentences, creating an almost unconscious rhythm to keep the attention of his audience throughout.

Creating an emotional beat

This, more than any other element of style, is self-evident. The work is half done if the speaker can take an audience on an emotional journey, orchestrating their highs and lows.

One way is to follow moments of levity with poignancy. Obama does this well at points in his speech, such as when he describes the provisions a marcher would need for a night behind bars, “an apple, a toothbrush, a book on government,” and follows with the enormity of the task they have set out to do.

Allusions and symbolism

Depending on how they are used, devices like symbols and allusions serve to lend a speech a level of grandeur, a level of importance beyond itself, by linking the present to past events.

In this speech, the most prominent symbol is the march itself. It is positioned as an inspiration for later similar movements, such as the one in Berlin, leading to the fall of its wall, and the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa.

The march at Selma saw violence intended to dissuade protestors from carrying on. Obama makes a point to connect the suffering of marchers to the trials faced by slaves in American history through the use of terms like the “North Star,” which slaves followed in their bid for freedom in the northern states of the country.

Elements of Substance

Elements that pack a punch and instantly connect you with your audience are essential in a political speech. They are:

- Reflecting on the present.

- A conversational start.

- The core message.

- The stories and anecdotes.

Let’s read on to learn them in detail.

Reflecting the present

Any political speech should hold up a mirror to the issues and happenings of the present. By showing that you understand these issues, you will put yourself in good stead to talk about solutions to them.

Allow your audience to trust you. That will occur when they realize that you and they are one and the same and that what they see is what you see.

A conversational start

It is often the case that you should ease into the topic of the day.

Start off with something one would say in a conversation. Avoid a grandiose tone or statement at the outset. If it sounds cheesy, you risk losing the audience’s interest. Find something natural to say that holds meaning to the voters so that the listeners do not think it is a rehearsed piece of text. Obama starts by showing his admiration for the previous speaker.

The core message

The takeaway from your speech may just be one short soundbite for a listener. Let that soundbite be the core message of the speech.

Time it so that the message hits the audience at the peak of their interest. Once hooked, the audience will open themselves up to what you have to say.

The stories and anecdotes

Speaking of events in your life or in the lives of others: loved ones, constituents, or people you look up to, can lay the tone of your speech and set the stage to relay a greater message.

A well-placed anecdote should help people relate to the speaker. Tell the audience what influences you to do the things you do. Talk about tough times that show you understand a voter’s circumstances or a grieving loved one’s pain.

Elements of Impact

Ethos, Pathos, and Logos

As put forth in Aristotle’s Rhetoric, 2300 years ago, the answer to how to write a political speech may be directly traced back to these three elements:

Ethos – The credibility of the speaker as perceived by the audience.

Pathos – The emotional connections you make with the audience.

Logos – The sound logical argument brought forth in your speech.

By having your audience buy into your speaker, their conviction, and their argument, you can leave a lasting impact. We can see ethos, pathos, and logos at work in the elements of style and substance as well.

By merit of being the first black president, Obama had established a level of ethos before even stepping on the stage. A further point of ethos within his speech is in the opening paragraph, where he calls John Lewis, a congressman who was a leader in the Selma march, “a personal hero,” establishing that Obama was a supporter of the struggle for civil rights.

Pathos can be found in the imagery evoked by the President throughout the speech. The telling of men and women who marched for their rights, steadfast in spite of “the gush of blood and splintered bone,” helped the audience identify with the courage of the marchers.

In his speech, he invokes logic to denounce the cynicism that he feels is rampant among youth today. He states that the march for voting rights from Selma to Montgomery could only happen because of the belief of marchers in the fundamental ability of the country to change for the better, such as in this line: “If you think nothing has changed in the past 50 years, ask someone who lived through the Selma or Chicago or Los Angeles of the 1950’s”

The build-up and repetition

Every speech should steer toward the central idea that serves as its backbone. Build up toward that idea through every anecdote or statistic you share. The audience’s mind may wander. The use of repetitions will enforce your idea in their minds. Studies in psychology suggest that repetition enhances cognitive processing and aids in information retention.

Here, repetition is used time and again to underline and explain various ideas in Obama’s speech, such as in this line where he underscores the qualities that he believes his country has, “The idea of a just America, a fair America, an inclusive America, a generous America.”

The note to end on

Depending on how you played your cards, this could be the point of the speech where you leave the most impact. Here, you can choose to twist the knife or administer the antidote.

As the speech nears its conclusion, impress upon the listeners the salient points of your speech. Make them think. And then conclude on a plaintive note or a joyous one:

“We honor those who walked so we could run. We must run so our children soar. And we will not grow weary. For we believe in the power of an awesome God, and we believe in this country’s sacred promise.”

Once done, It is time for the speaker to retire and the audience to stand at attention for perhaps a moment longer, spellbound.

And that is how every great speech inevitably ends.

Featured Image Source: Mikhail Nilov